Project Name:

Humanitarian Passport

Country:

World

Agency:

Humanitarian groups offer critically needed aid and assistance, often working in difficult and dangerous environments and under intense pressure. Unfortunately, some use these opportunities and the positions they hold to exploit the people they are supposed to protect and to corrupt the systems they are supposed to help.

In 2018, the aid sector was rocked by an abuse scandal after reports that senior Oxfam staff members paid survivers of the 2010 Haiti earthquake for sex. An inquiry soon expanded to cover other N.G.O.s, including Save The Children, The Red Cross, and the U.N., threatening to derail the entire charity industry.

The scandal grew large enough that entire countries began to bar N.G.O.s from operating within their borders. By 2018, Haiti had barred Oxfam from working within its borders over concerns the charity was unable to investigate and identify predators within its ranks. There was a clear crisis of trust facing both the countries and the N.G.O.s; it became clear the N.G.O.s needed a new way to vet its workers with increased transparency while giving the countries a way to rebuild their trust in the N.G.O.s.

Challenge

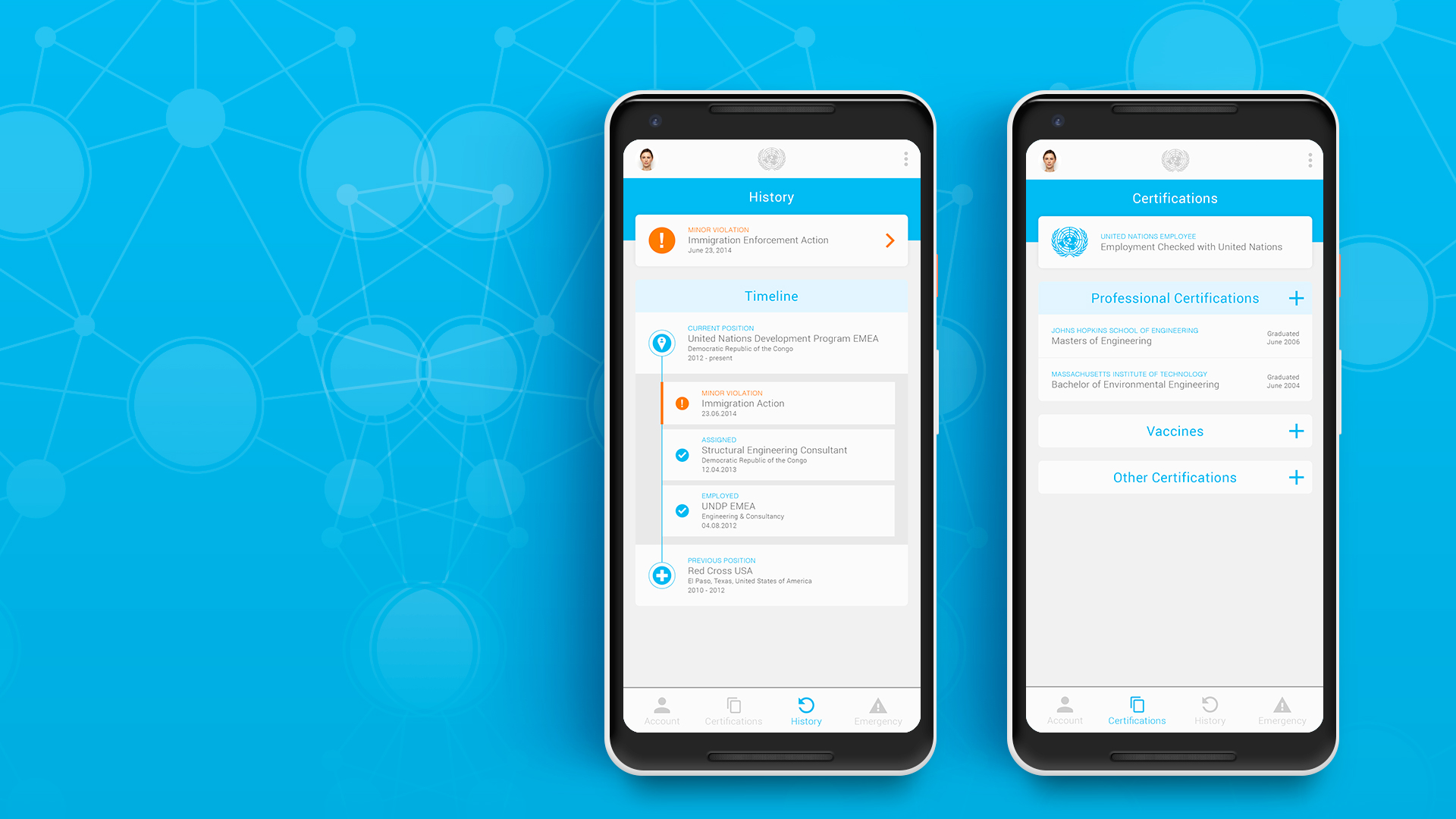

We needed to create a tool where aid workers could demonstrate that they had a clean background and work history, even if they were in areas of low- or no internet connectivity. It would need to be highly transparent yet highly secure, with user work history verified in a country non-biased way. The platform would allow governments to make on-the-spot decisions about the background of an aid worker, then accept or reject their ability to operate in that country. Previously, countries had few, if any, resources to quickly and verifiably check the backgrounds of N.G.O. workers; this new platform would end the power imbalance between the workers and the countries in need.

The three major obstacles we faced included:

- The raw source of our data. We could not be involved in investigating or judging the aid workers. We needed a partner who could review any allegations of misbehavior and submit reports.

- How to store the data in a format that, when viewed, would be considered as the truth by a local authority. Its verification had to be immutable and non-biased, and changes and modifications to the data set needed to be recorded.

- An ability to confirm that the person presenting the background check was the person in question, not someone impersonating them.

Development

My innovation team spent an accelerated five-week development cycle, creating a platform that would provide an instant and secure record of an aid worker’s past.

Data Source

Karakoram could not be involved with the investigations into aid workers or involved in the judgments for or against them. As part of the U.K. Government’s Operation Soteria, we were offered access to Interpol as a primary data source.

Data Storage

Blockchain, a non-biased and immutable way to store read-only data, was picked as an ideal database choice for recording pre-vetted information about workers. The ability to view any submitted data points, as well as any changes, formats this information without preference to any specific country, bloc or alliance.

Data Confirmation

One of the biggest challenges was how to tie data to a specific user in a verifiable way. In an ideal world, the best solution would be adding a digital page, including an aid worker’s verified work history, to their passport. Because border security already has to verify the identity of a passport holder, checking this new digital page would be a natural extension to existing behavior.

Getting 200+ countries to add this digital page to a country was not feasible. Still, our team thought there were other ways to connect the passport to a digital application in a verifiable way.

The breakthrough came when our team discovered a way to synch and read the R.F.I.D. chip in all modern global passports and other I.C.A.O.-compliant identity documents. By scanning the Machine Readable Zone, we were able to gain access to the embedded chip, including all biometric and biographical data contained within, including name, home address, passport ID photo, expiration dates, and passport number. We were able to verify passport authenticity through security checks, such as Active Authentication, Document Signature Validation, and Country Signature Validation, and prove authenticity of the document.

Linking a user account to an aid worker’s travel document, and logging into existing user background databases, included a secure three-fold authentication method:

- Scanning the user’s passport optically, proving they have physical control over the document. Using Optical Character Recognition we were able to digitize and capture the passport’s I.D. number.

- Verification and scan of the embedded passport R.F.I.D. chip, confirming that the passport I.D. on the chip matches the scanned number.

- The input of a unique passport and fingerprint scan on appropriate devices. After all three verification steps are completed, border control agents could view and verify the employment history of any aid worker coming into their country.

GDPR Compliance

We had to consider G.D.P.R. compliance when creating the prototype, as it contains a high amount of personal data. We were unable to collect, process or store any data from people living in the European Union, which included a large number of U.N. field workers.

G.D.P.R. restrictions prohibit the use of personal data retention, defined as “... any information that relates to an individual who can be directly or indirectly identified. Names and email addresses are obviously personal data. Location information, ethnicity, gender, biometric data, religious beliefs, web cookies, and political opinions can also be personal data. Pseudonymous data can also fall under the definition if it’s relatively easy to ID someone from it.”

As a result, we designed our platform to limit the personal data stored within remote servers. Due to our user experience design of requiring a passport R.F.I.D. scan on each login, we were able to create a system that wipes all biometric information - including names, photos, addresses and dates of birth - on each logout. The cloud retention was limited to a hash encrypted copy of the passport I.D., as well as an encrypted copy of the aid workers’ background, with all personal identification removed. For each login, if the passport hash matches an account and a hash on record, the individual user information would be re-downloaded from the R.F.I.D. chip. We were able to maintain all G.D.P.R. non-compliant data safely where it belongs: on the aid worker’s passport.

Result:

By requiring all U.N. workers to show the Humanitarian Passport as an addendum to their travel documents when entering a disaster, development or aid zone, each worker is held to the same standard. However, after a period of initial enthusiasm from the aid sector, partners dropped out of the program due to internal pressure. Ultimately, our final partner, the U.K.’s Department for International Development, bowed out, with the British Development Secretary, Alok Sharma, concluding: “There is no real consensus … I don’t sense that right now that there is the appetite internationally for us to be setting up this international ombudsman.” Rory Stewart, the former U.K. development secretary, said it was not D.F.I.D.’s job to be an “international policeman.”